Reprinted from the newsletter of First Mennonite Church, Edmonton, Alberta. The author attended the United Nations’ climate change gathering in Morocco in November 2016 and reported back to his congregation as follows. Randolph Haluza-DeLay teaches sociology at the King’s University in Alberta.

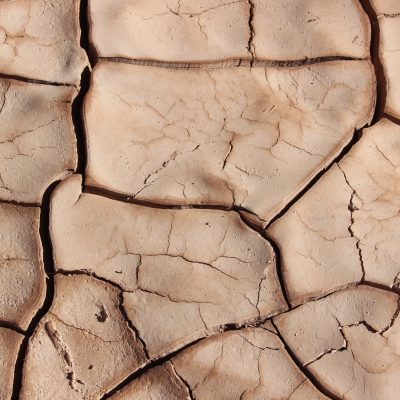

There is a connection between the Syrian family that First Mennonite Church is supporting and my attendance in November at the United Nation’s ongoing international negations on climate change. Drought in Syria was prolonged by climate change and increased political instability.

Research published in top journals shows climate change has changed precipitation patterns in Syria, reduced water storage, increased over-grazing, increased stress on families, decreased the financial and political capacity to absorb the greater needs of the population and provided fertile ground for extremist groups and war. Syrian refugees are political refugees. But they are also climate refugees.

Climate change multiplies threats

Climate change is a “threat multiplier.” That is, in societies where there is less capacity to absorb natural or social crises, the changing climate will cause extra pressure, worsening these weaknesses. Climate change is a peace issue. And since the greenhouse gases have been produced mostly in the industrialized Global North, climate change is a justice issue. At the invitation of the World Council of Churches, I became an officially accredited observer for the annual negotiations on climate change in November 2016. These meetings are under the auspices of the United Nations. The participants included official and unofficial representatives of national governments, provincial and local governments, people’s groups (like the World Council of Churches), business associations and others. It was certainly not just environmentalists. There were even climate deniers there.

Because most of us believe that caring for creation and its people matter, there was much in common. There were differences, too. I witnessed a memorable argument about social justice between European labour leaders and African activists. It was at a session on a socially “just transition” for European coal miners. If we are to transition away from fossil fuels, we need to ensure workers and their families are taken care of, which means a transition taking a decade or two. “But your justice will kill us,” the Africans argued. “WE need climate justice NOW! We need coal phased out by 2023 or our communities will have even more drought and death.” There are no easy answers, even with a mutual commitment to social justice and caring for people.

Global Work

I looked into the eyes of a sister from the Philippines who talked of Typhoon Haiyan and other storms killing thousands. I listened to youth from the Lutheran World Federation affiliates in several African countries report on decades of sustainable agriculture, forest management and interfaith cooperation being erased by changing climates. I talked with a Korean Buddhist nun and a Korean Franciscan priest coordinating a national council (and who had both read my very academic book on religion and climate change!) This work is global work.

The two biggest takeaways for me are how detailed these negotiations are and how faith-based actors play in. They have had a very significant role in civil society for many years, and were essential in bringing attention to issues involving fairness and justice. Increasingly, faith-based organizations are magnifying their efforts through interfaith coalitions.